What is refractory Celiac Disease?

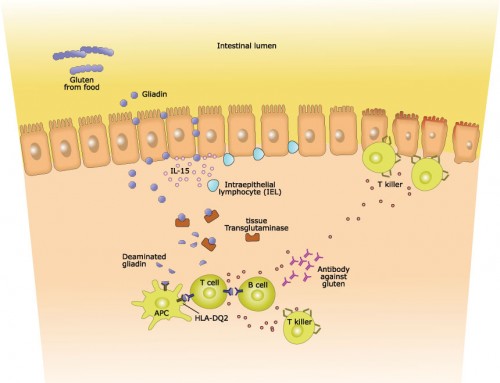

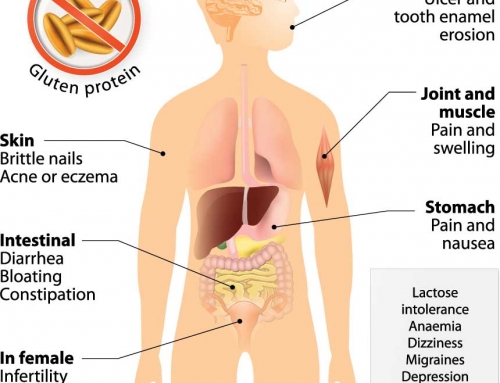

The aberrant immune response causing celiac disease is triggered by the consumption of gluten. In most cases, this immune response stops after the complete removal of dietary gluten, and the intestinal lining is gradually restored. As the intestine returns to a healthy, normal state, the celiac disease symptoms decrease and the adequate absorption of nutrients can occur. However, in a small proportion of cases, the immune response and the intestinal damage continues, despite the removal of gluten. This unresponsive form of celiac disease is called “refractory celiac disease” (RCD).

Diagnosis of RCD

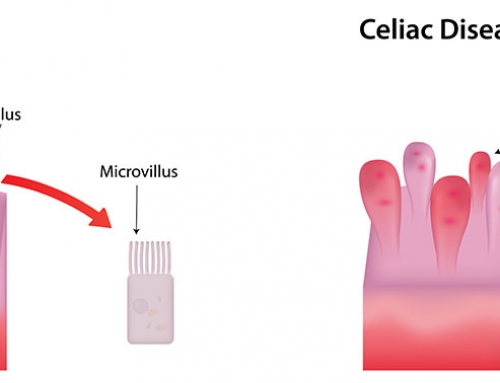

The current definition of RCD is “the recurrence or persistence of malabsorptive symptoms and signs with villous atrophy despite a strict gluten-free diet for >12 months”. Unfortunately the accurate diagnosis of RCD is complicated, and hence it is difficult to correlate data from different institutions, studies and clinical trials.

RCD diagnosis can be affected by the variation and even absence of “classical” gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. weight loss, diarrhea, bloating), despite severe damage in the intestine. Many of the typical celiac symptoms also occur in other health issues (e.g. irritable bowel syndrome or chronic norovirus infection), again complicating an RCD diagnosis. Changing to a strict gluten-free diet is also extremely difficult, as gluten is found in many different foods, medications and even some lip balms! Some celiac patients do not actually have RCD, but are highly sensitive to even tiny amounts of gluten and the intestinal damage continues.

Genetics of RCD

Although there have not yet been any genetic markers of RCD identified, there does appear to be an increased risk of elevated gluten sensitivity in people who have two copies of the celiac-associated HLA-DQ2 complex. The DQ2 heterodimer (formed from HLA-DQA1*05 and HLA-DQB1*02) is present in the majority (90-95%) of celiac-affected individuals, but many of these individuals only have a single copy of the DQ2 complex. The predisposition of DQ2 homozygotes to elevated gluten sensitivity may also be linked to an increased risk of RCD.

Types of RCD

There are two types of RCD, further complicating an accurate diagnosis and adequate therapeutic response. Type 2 RCD (RCD2) patients have an excess of an aberrant population of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, while RCD1 patients do not have a large number of these aberrant lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are a type of white blood cell that are important components of the immune system, but the aberrant population in RCD2 patients is linked to a devastating intestinal cancer – enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. An aggressive therapeutic approach is essential in RCD2 patients to help prevent the transformation to intestinal cancer. However, the evaluation of the aberrant lymphocytes can be very difficult, as they are also present in many RCD1 patients and even healthy individuals. It is the confirmation of the increased proportion in RCD2 patients that is critical for an accurate diagnosis.

Treatments for RCD

Corticosteroids are generally the initial treatment option for both RCD1 and RCD2. Usually the steroids reduce the celiac symptoms, but several studies have shown that they are not always effective at actually helping to repair the damaged intestinal lining. Long-term steroid use also poses a high risk of steroid dependence, where the patient develops a physical or psychological dependence on the drug. Various different steroids and combinations are currently being analyzed with some showing very promising results, but longer-term follow-up is still required.

Up to 67% of RCD2 patients develop enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. The survival rate for this lymphoma is only 15% at two years; hence more radical therapies for RCD2 patients are often considered. Autologous haematopoeitic stem cell transplantation is one such approach that has shown promise. However, it does not completely remove the risk of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, as some of the aberrant lymphocytes still remain.

New treatment options are continuously being developed and tested for various inflammatory conditions and many of these may also be effective treatments for RCD.

References:

Al Toma A, Goerres MS, Meijer JW, Pena AS, Cruius JB, Mulder CJ (2006). Human Leucocyte antigen-DQ2 homozygosity and the development of refractory celiac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 4(3): 315–319.

Al Toma A, Visser OJ, van Roessel HM et al. (2007). Autologous haematopoeitic stem cell transplantation in refractory celiac disease with aberrant T cells. Blood. 109(5): 2243–2249.

Ludviggson JF, Lefler DA, Bai JA et al. (2013). The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut. 62(1): 43–52.

Woodward J (2016). Improving outcomes for refractory celiac disease – current and emerging treatment strategies. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 9: 225-236.

Genovate Laboratories2017-04-06T19:04:51+00:00